In many urban centres in sub-Saharan Africa, popular art movements developed in the 1960s, after the end of the colonial period, especially in music and painting, but also through comics. Starting from a heterogeneous audience, these currents were oriented neither towards the traditional culture of the respective region nor towards the European-influenced, elitist culture of Congolese intellectuals. Popular art rather arises from a collective consciousness and in turn reflects, archives and develops collective thinking. The reception of popular Congolese art in Europe is mostly limited to an ethnological or sociological interest, which reduces the works to a purely representative value. The actual significance and complexity of popular art production is thus often underestimated, as Jean Kamba wants to show in his essay.

So-called “Popular art“

from Jean Kamba

I’m the one who gave our painting the name “Popular Painting” . When I set up on my own, I heard that I was doing naive painting. I looked it up in the dictionary and thought that it didn’t suit me. The word “naive” didn’t interest me too much and I preferred the word “popular” which came to the fore and was adopted by everyone. It’s a painting style that stems from the people, concerns the people and is addressed to the people. It is immediately understood by everyone and the people recognise themselves in it.1

ChÉri Samba

In the ambiguity and diversity of our remarks, popular art seems to me to be, at most, an artifice which, in reality, does not correspond to any precise field. Returning to the analysis of this vague concept should probably enable us to better grasp the complexity and contradictory social functions of art in Zaire.2

Y.V. Mudimbe

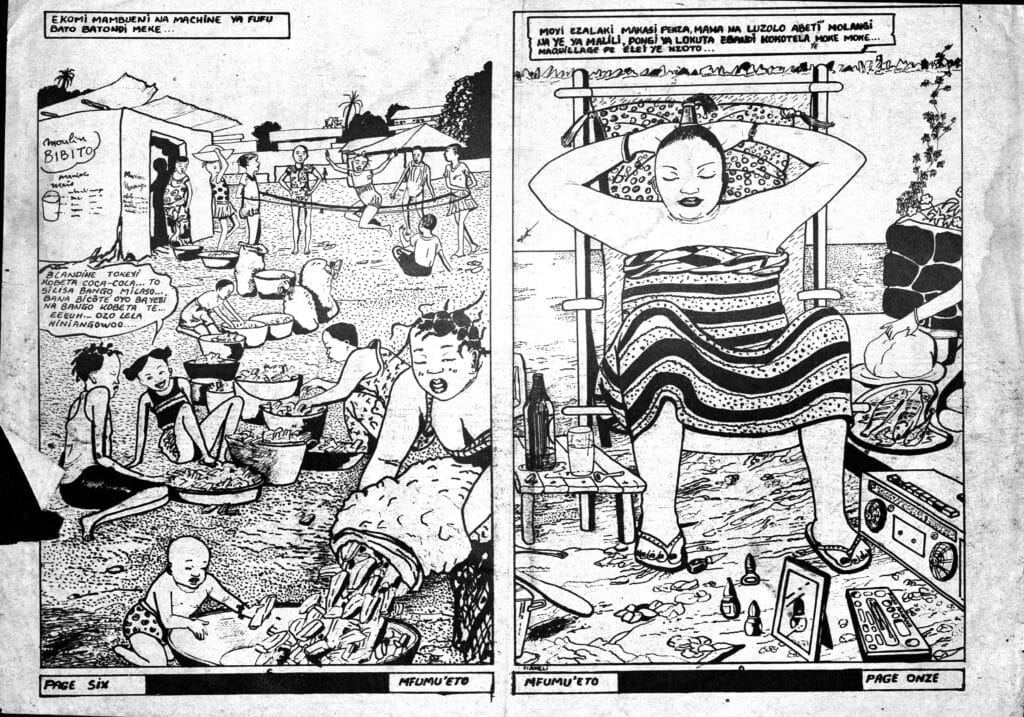

What it’s all about: Street scenes / A woman organises her sales stand and dresses up.

Middle left: “Blandine, let’s play the game Coca-Cola (raffle with plastic bracelets as a stake). Then we all win plastic bracelets. The other kids over there are not good at the game! Why are you crying?” (translated from the language Lingala)

These two quotes show how much the concept of popular art in the DR Congo – which includes so-called “popular” painting, “popular” comic strips and “popular” music – remains a vast field to be explored, and its current classification remains questionable.

Cassiau-Haurie sees in the so-called “popular” comic strip “the reflection of urban culture, made up of inexpensive, hand-crafted booklets that are distributed on the ground in the ‘librairies par terre’ (street bookstores)”.3 And he adds: “These very modest magazines, published in Lingala, are distributed outside the traditional bookstore circuit.”4 Furthermore, Alain Brezault while describing the works of comic strip artist Lepa Mabila of the 1980s, talks about “pamphlets as poorly printed as those of Mfumu E’to, that express in a lighter tone than his colleague, the problems and difficulties of daily life encountered by the inhabitants of the various districts of the capital.”5

In the logic of Marco Meneguzzo, – speaking of popular art, which he classifies as “ethnic”, referring to a painting by Chéri Samba – “It is an essentially narrative figuration that evokes both popular art and Pop Art itself”.6 According to Meneguzzo, the “ethnic” character of popular art is justified by the fact that “Chéri Samba adopts the popular imagination of Central Africa to tell, in images and with long didactic inscriptions, the events and preoccupations of this culture.”7

On the other hand, Mudimbe while speaking about a vague concept that should be questioned and analysed in depth in order to perceive and grasp the “complexity” and “contradictory social functions” of art in his society, opened the way to a universe that is not satisfied with a mere superficial reading, but on the contrary requires a field of investigation that calls upon the skill of a tightrope walker in order to be understood.

Cover picture of the comic / Conflict between the second wife and the child of the first wife // Title: “Real rivals” / Above: “You only bought the new school uniform for Blandine and the Gold Princess, not for me.” / Middle: “What’s wrong?” / Bottom: “Shut up!” / Subtitle: “Take good care of your rival’s child / No to divorce”

But today there are terms and adjectives that are associated with so-called popular painting or comics; adjectives that nevertheless contrast with the nature and elements of these artistic productions. Let us note that we are talking here about the productions of so-called “contemporary” popular art, painting and comics, that is to say a period from the 1970s, the period of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, to the 1990s, that of Mfumu’eto.

The above-mentioned set of terms, epithets and designations, which do not do justice to these plastic artistic expressions, are for example: “poorly printed comic strips”, “urban culture”, “everyday life”, “crafts”, “poor materials”, “naive and ethnic works”, etc.

These language instruments have long and vainly attempted to destroy the soul and raison d’être of these cultural phenomena, de-contextualising them and at the same time caricaturing them and stripping them off of their major dimension as works that transcend everyday life. Fortunately, these mediums do not need a context because they themselves are rooted in the diffusion of sensitivities, especially among their local consumers.

On the plastic and artistic level, these productions testify and bear witness to artistic creation in form and substance. No, they were not badly printed; they were printed as required by and according to their nature. The simplicity of communication and easy access offered by the medium of paper enables an artistically sound approach inspired by the collective imagination and social gravity – giving these works a system of complex codes that go far beyond their direct social context. These burdens were caused by a history (political, religious, economic, etc.) that was responsible for and presided over the conception of a post-independence Congolese identity.

These artistic manifestations appeared, went around the beaten track and asserted themselves among a population thirsting for new stories and heroes. A population in search of a mirror, nourished by the same stories and legends that furnished its daily life and allowed it to see itself in the mirror. A path towards attempting to erase artistic references that had been considered canonical until then. What could be more normal than to cross out from the list of backward expressions those artistic productions that inspired a transgression in the face of traditional conformism, both formal and conceptual, imposed in the conception of a painting or a comic strip.

Mfumu’eto said:

I was aiming for the widest possible audience. The literate, the semi-literate, the illiterate, the intellectuals, the illiterate, in short, everyone. Only I gave a slight priority to women and children. At the time, many intellectuals considered that Mfumu’eto Magazine was exclusively for children. But as time went by, my magazine arrived in homes and in the imaginations. Adults, the famous intellectuals, started to look at it and then started to read it.9

Mfumu’eto

It should be noted that the so-called popular comic strip, as well as the so-called popular painting, experienced a peak period in Congolese society. Currently, these mediums are becoming rare on the local scene.

Mfumu’eto is today, by the force of time and market, presented as a “contemporary artist” in exhibitions internationally, his boards are sold and exhibited in a very different way than in the 1990s, when his success was measured by its readership among Congolese of all strata and when they were still accessible, both in form and substance.

These were cultural products sold in “wenze”10, laid out on the ground and accompanied by shouted-out comments from their seller. The mothers, after their shopping, would be able to buy a new issue at an accessible price and read it with their families.

But there are still some actors who continue to work in this direction, despite the change in the political and social context. This is, for example, the case of Rocky production.

What it is about: A woman ensnares a man and takes him into the invisible, spiritual world

- See ‘Interview with Chéri Samba’, in: MAGNIN, A. (Ed.): Beauté Congo 1926-2015 Congo Kitoko, Paris, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2015, p.189.Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- MUDIMBE, V.Y.: 1992. ‘Et si nous renvoyions à l’analyse le concept d’art populaire’, in: JEWSIEWICKI, B.(Ed.): Art pictural zaïrois (coll. Nouveaux Cahiers du CELAT), 1992, pp.25-28. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- CASSIAU-HAURIE, C.: Histoire de la BD congolaise. Paris, L’Harmattan, 2010, p.79. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- Ibidem. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- Quoted in ibidem, p.81. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- MENEGUZZO, M.: L’art au XXe siècle II. L’art contemporain, Paris, Hazan, 2007, p.139. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- Ibidem. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- HUNT, N.R.: “Papa Mfumu “Eto 1ier, star de la bande dessinée kinoise”, in: MAGNIN, A. (Ed.): Beauté Congo 1926-2015 Congo Kitoko, Paris, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2015, p.226. Translation of the quotation into English by the editors.

- Sort of market in Kinshasa where you can find various products.