On his deathbed, Copernicus published the book that founded modern astronomy.

Three centuries before, Arab scientists Mu’ayyad al-Din al-‘Urdi and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi had come up with the theorems crucial to that development. Copernicus used their theorems but did not cite the source.

Europe looked in the mirror and saw the world.

Beyond that lay nothing.

The three inventions that made the Renaissance possible, the compass, gunpowder, and the printing press, came from China. The Babylonians scooped Pythagoras by fifteen hundred years. Long before anyone else, the Indians knew the world was round and had calculated its age. And better than anyone else, the Mayans knew the stars, eyes of the night, and the mysteries of time.

Such details were not worthy of Europe’s attention.

From: Eduardo Galeano, Mirrors. London: Portobello Books, 2009 (2008).

Europe looked in the mirror and saw itself reflected in a Retina display. Beyond the high-res picture of itself, the rest of the world was reduced to scraps of visual content. Pixelated, forever buffering, and painfully compressed – the visual economy created by Eurocentric logic, renders the world beyond the mirror into something worse than nothing. Sad itinerant copies of what it deems to be the original image, namely itself.

This text takes its point of departure from the artist and theorist Hito Steyerl’s text “In Defense of the Poor Image” from 2009. Her writing merges the succinct critique of neocolonialism, with a bold analysis of contemporary audiovisual culture. Within the context of the Popular Images platform, Steyerl’s account lends itself well to a discussion of the political potentiality in popular images produced and distributed in Congolese society. There are many apt examples on the digital platform which would mobilise a conversation on how comics and popular visual culture transgress the boundaries of merely “poor image” production, but for the sake of this text, I have chosen to highlight the prolific activities of Rocky Production. Introducing the concept of the poor image, Steyerl writes:

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.[1]

Steyerl’s quote above speaks well to the Eurocentric hierarchy of image production, but also to that same visual system within contemporary art. Video works, digital photography and hour-long Zoom conferences hinge on the velocity and availability of high-speed internet. Within the context of contemporary art making, the artist duo Christ Mukenge and Lydia Schellhammer note that the internet is a boundless space of opportunity for some, while for others it remains largely inaccessible due to low quality and high connection costs.[2] Run by Silicon Valley tech-oligarchs, the experience of the internet as a libertarian dreamscape is restricted to those with the devices and technological infrastructure to access it. The high-resolution image becomes a prized fetish, a visual experience only available to the select few. Steyerl adds that the “… contemporary hierarchy of images, however, is not only based on sharpness, but also and primarily on resolution.”[3]

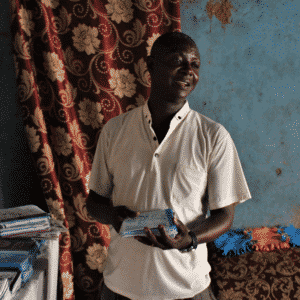

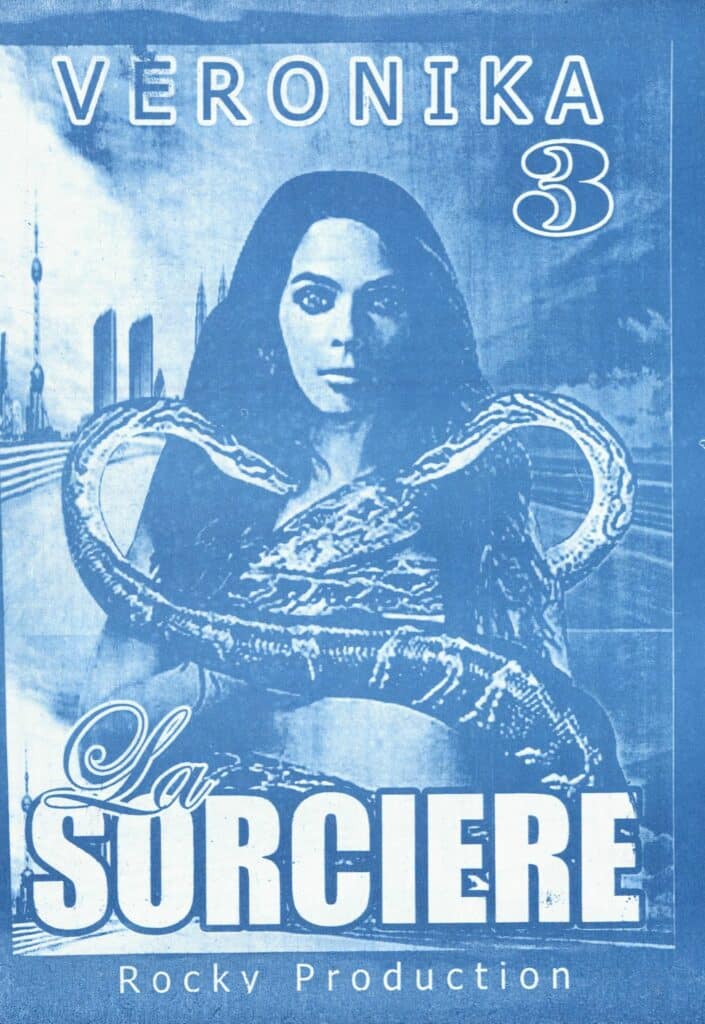

However, in the poor image, she also finds the political potential as well as the historical legacy of the left. The low-res image, is an image that can be made and seen by the many. Hailing back to the political pamphlet and agitprop, the poor image is therefore a popular image, she argues.[4] Referring to the comics of Rocky Production, they echo Steyerl’s insistence on the importance of the popular image, as one in which the boundaries between author and audience are blurred and where life and art are merged. In the videos on the platform, the audience is taken on an exhilarating journey through the neighborhood of Bumbu, Kinshasa, following Shekinah Kashama Mfumba, in producing the comic strip “The Sorcerer kills a Fetishist”. Not only is the content of the Rocky comics worthy of extended discussion, but also the mode in which they are produced. The distinction, boldness of the images, and color vibrancy are achieved through the process of screen printing. Gelatine is applied to the metal plates to adhere the color, while the print itself is made with a Heidelberg Offset Machine.

The history of printmaking is firmly connected to the political pamphlet and the underground zine, as a modality in which to quickly disseminate popular and political ideas in society, with oftentimes, accessible materials. Boloko ya bolingo (“The Love Prison”), the latest comic series by Rocky, draws on the folk stories of popular theatre in Kinshasa, which is also an art form explored prior to Rocky Production. Moreover, the work of Rocky Production also acts as a powerful rebuke to the Western colonial claim to universalism and its ocularcentric view from nowhere. In the words of the feminist scholar Donna Haraway, “[v]ision in this technological feast becomes unregulated gluttony; all seems not just mythically about the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere, but to have put the myth into ordinary practice.”[5]

Speaking directly to this quote by Haraway, Rocky Production departs from the post-independence Congolese context, where the comics hold a mirror to the need for a new collective imagination; of novel stories, contemporary heroes and modes of distribution.[6] Furthermore, the highly skilled production of these comics also speaks to a form of situated knowledge, where the serigraphies are archived through metal plates which do not decompose in the tropical climate. The case study of Rocky Production asserts the argument by Steyerl, that the popular image transgresses the boundaries of Western cultural narratives both in terms of artistic quality and mode of distribution. As such, it defies the Western technological “cannibaleye”[7] seeking to transform everything into lesser copies of itself.

To complement the text, two covers of the Rocky Production comics:

© Rocky Production

© Rocky Production

[1] Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” e-flux, e-flux Journal #10, 2009, www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/. Accessed: 20 May 2021.

[2] Mukenge/Schellhammer, et al. “Foreword.” Laboratoire Kontempo 2020, edited by Beya Othmani, 2020, p. 5.

[3] Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image.”

[4] Ibid.

[5] Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1988, p. 581.

[6] Kamba, Jean. “Popular Comics and Collective Imagination.” Popular Images, 27 July 2020, popularimages.org/en/blog/popular-comics-and-collective-imagination/.

[7] Haraway, “Situated Knowledges”, p. 581.

Guest author in this article: OLIVIA BERKOWICZ

Homepage: http://oliviaberkowicz.com/

Instagram: @oliviaberkowicz